Vasyl DUDKO

(Dnipro, UKRAINE):

“68 FAMILIES WERE FORCIBLY

RELOCATED FROM OUR VILLAGE…”

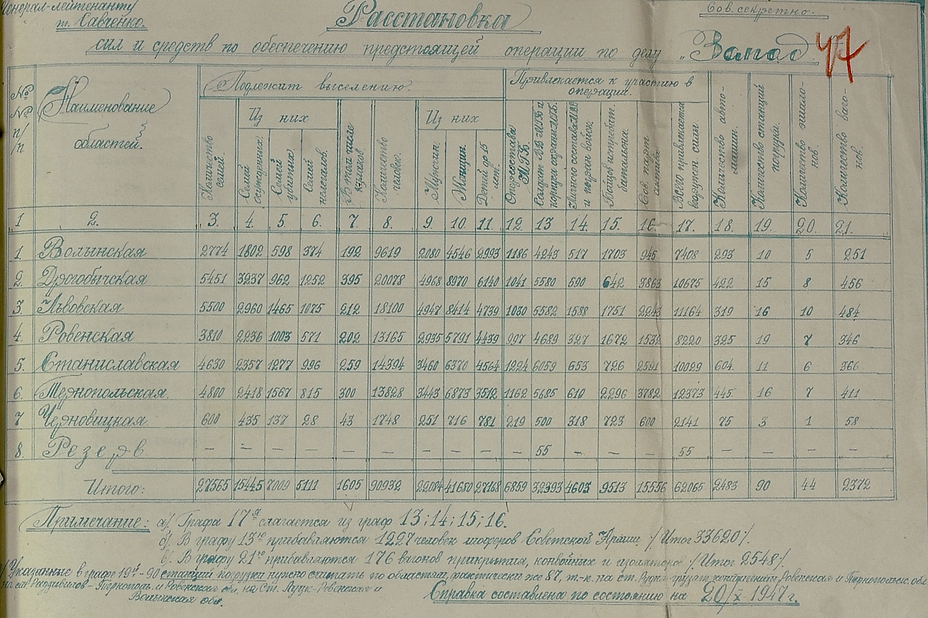

Ukrainian and Russian sources provide different estimates of the number of people affected by repression, famine, and deportations in Ukraine. According to the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory, this concerns 10-20 percent of Ukraine's population—between 4 and 7 million Ukrainians. According to Russian sources, it's 2-3 million. In any case, the number of victims is measured in millions…

I was born on June 17, 1958, in Camp No. 3, Zeya District, Amur Oblast, Russian Federation. My parents were repressed during the mass deportations of Ukrainian families from western Ukraine to the Far East.

My father and mother, along with my grandfather and three-year-old Anna, my older sister, were taken to Amur Oblast. During the journey, my sister fell ill and nearly died. As a result, she had to learn to walk twice – once after being born and again after recovering from her illness. They traveled for two months, enduring the cold. My uncle Dmytro received 25 years in the camps and helped build Norilsk. He was there with his mother, my grandmother. My aunt, my mother's sister – the one who was a liaison in the UPA (Ukrainian Insurgent Army) – served 25 years in Northern Kazakhstan. The entire family was repressed.

The entire family was repressed as a cautionary example to intimidate everyone. 68 families – 360 people – were forcibly relocated from our village. This village is Bratyshiv in Tlumach District, Stanislav (now Ivano-Frankivsk) Oblast, forty kilometers from Uhryniv, the birthplace of Stepan Bandera. Young people and older residents joined the UPA units, providing various kinds of support – carrying food, sewing clothes... There was widespread support for the UPA here.

Later, there was a blockade, with soldiers stationed in every village, checking everyone as they left. This is from the stories of my parents and relatives. For instance, when people went out to work their fields with horses, the carts were inspected to ensure they weren't carrying water or food for the UPA. People from the hamlets were relocated to the village to prevent any support for the UPA. They fought for independence.

Our village suffered greatly during the war; the front line passed through it, and it was bombed and shelled with artillery. Three-quarters of the village was burned down. My grandmother died on Easter in 1944. That day, the Soviet air force bombed the village three times because there were a few Germans there. People were hiding in shelters, but it was Easter. People wanted to go home; a man wanted to shave and put on a clean shirt... People were very devout. They were discouraged from going out, but when everyone fell asleep, they went outside. They had only walked a few dozen meters when the attack planes came – my grandmother Anna was torn to pieces. When it finally quieted down, my grandfather gathered what he could find of her remains, placed them in a shell box, and buried her. He never remarried, even though he was still young, only 46 years old at the time...

And then, after the 20th Congress of the Communist Party, in the late 50s, rehabilitation notices started arriving, and many people moved to Sievierodonetsk. One person went, and everyone followed. Late 50s, early 60s. Few Ukrainians stayed there. They weren't allowed to return to their homeland. There was a prohibition, they simply weren't allowed. They would visit the village they were deported from, but without registration, without a job, there was nothing for them. This was an unwritten rule. I am speaking from the accounts of my relatives and close ones, this is how it was.

– You were born after these events. Your parents told you about them. Since when? When did you realize you were Ukrainian, living in Russia?

– Our parents didn't tell us anything about those events, fearing we might talk about it at school or elsewhere. But they whispered among themselves... It was only during perestroika in the 1980s that we gradually learned about it. In 2011, I visited our village upon invitation to participate in events dedicated to the 100th anniversary of the famous sculptor Hryhorii Kruk.

From Wikipedia: Kruk Hryhorii Yakovlevych (also: Hryhoriy Kruk, German: Gregor Kruk, October 30, 1911, Bratyshiv, now Ivano-Frankivsk region – December 5, 1988, Munich, Germany) was a Ukrainian sculptor and graphic artist who worked in Germany. The main theme of his work: the historical fate of Ukraine – more than 300 sculptures of various formats; among the sculptural works are "Portrait of Patriarch Joseph Slipyj", "Nun", "Rest", "Peasant Couple".

He is our relative on my father's side. On October 31, 2011, a sculptural bust of him was installed in the village. A prayer service was held, and attendees visited the site where the family estate used to be, although it no longer exists. Two oak trees were planted there, and a concert took place in the community center. As one of the two remaining relatives, I was invited to this ceremony.

– How did you settle in Dnipro?

– For the first time, my mother and I visited Ukraine on vacation in the summer of 1973 for two months. Four of us brothers were born in the Far East. We visited Sievierodonetsk, Komunarsk – where my uncle, an artist, lived. We visited Bratyshiv in Western Ukraine. The following year, we moved permanently, and my parents bought a house in Sievierodonetsk. They didn't dare return to their native regions because it was impossible to register or find work there. I finished the 10th grade in Sievierodonetsk and entered the mining technical school in Lysychansk. After one year, I was drafted into the army, serving as a tank crewman for two years. After that, I got married and worked in the mines for 12 years in the Luhansk region. After my divorce, I moved to Donetsk and continued working in the mines. In 2014, when Russian occupiers came to Donetsk, I moved to Dnipro. And when the full-scale war began in 2022, my ex-wife, daughter, son-in-law, and five-year-old grandson also moved here.

In 2016, I became a volunteer. I worked in a rest area for transit military passengers at the central bus station in the city Dnipro. I was involved with the Cossacks – Kodatska Palanka, Starosamarska Sotnia of the Zaporozhian Cossack Host. We knew that war was coming and were organizationally prepared. As soon as it started, we immediately began to help: mobilizing the first reserve, assisting the wounded in hospitals. Later, I volunteered for a three-year contract. We went through training at a training ground and were sent to the area near Zaporizhzhia, where we were assigned to sorting, given weapons, and told that those over 60 were to remain in the rear.

“War is the business of the young, a remedy for wrinkles,” as Tsoi sang. That's why we formed a counter-sabotage company here, catching saboteurs and spies, and helped in the formation of the 108th and 128th Territorial Defense Brigades in the early days. Then we established a training center for military preparation on a volunteer basis and trained fighters in 11 disciplines through voluntary two-month courses. We have received many thanks from the fighters who went to the front well-prepared.

This is an air raid siren. We are already used to it, we won't leave? War… Two different peoples, two different mentalities. Why is this same gene...

– Maybe it’s historical memory?

– Of course, it’s historical memory. When we were in exile and went to school, we studied alongside the children of exiles from the Baltic countries—Latvians, Lithuanians, Estonians—as well as Belarusians, Moldovans, and many Ukrainians. Our settlement had an eight-year school, and for the ninth grade, we were taken to a boarding school 30 km away. That settlement was two to three times larger, and it was also predominantly populated by Ukrainians. They were cutting timber. That camp was later renamed a forestry station.

– Tell me, what language did you speak there?

– Of course, everyone spoke Russian. The older people spoke their own languages—Ukrainian, Belarusian, Lithuanian… My mother subscribed to the magazine "Soviet Woman" in ukrainian, I read it, I was generally fond of reading. My mother sang songs when I was little, in the cradle... And I was good at languages — I served in Poland and learned Polish in two years, I spoke very well. I know German because I studied it in school and at the technical college.

– Tell me, will we win?

– Of course, we will win. But this nation also matures — our people chose war when they chose Yanukovych.

– Have many of your acquaintances died?

– Well, yes, there are losses. Acquaintances, friends, are fighting... About 5% out of 100.

– Victory is coming. Glory to Ukraine! Glory to the heroes!